Four lessons research-led writers can learn from poets.

What’s poetry got to do with research-led writing?

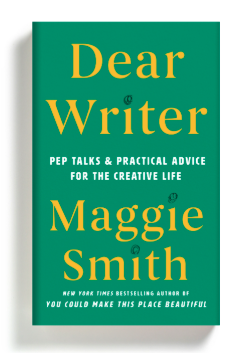

Over the last couple of months I’ve been listening to the audiobook version of Dear Writer by Maggie Smith, which promises on its cover ‘pep talks and practical advice for the creative life.’ In the book’s blurb Maggie cleverly neglects to say she’s a poet who will be talking a lot about her poems. I say cleverly because If I’d seen that, I wouldn’t have bought the book, and I suspect I am not the only one. In fact, when I heard Maggie say this in her introduction, I must confess to a mild eye-roll and a micro-sigh as I mentally consigned Dear Writer to my ‘unfinished’ list on Audible.

I am not a poet and don’t want to write poetry, so why would I want to read/ listen to this book? But I was listening on the motorway and couldn’t turn it off, so listen I did. And listened, and listened, and listened.

Isn’t it brilliant to be proved wrong? I love that feeling of having my mind changed by an eloquent argument and brilliant logic, and that’s what Maggie Smith does in this book. As (arguably) one of the more inaccessible forms of writing, poetry isn’t as popular as prose. Despite enjoying writing little rhymes and finding powerful meaning in song lyrics as a teenager, at school I was forced to read puzzling, antiquated poems and always felt poetry had a whiff of elitism about it. Whatever the reason, poetry has never really floated my boat, but in Dear Writer, Maggie Smith patiently showed me how all prose is poetic in some way, even research-led writing, and how useful the poet’s toolkit can be for all writers. After all, even a scientific article has its own cadence, with words carefully selected for precision and objectivity.

So here are four lessons research-led writers can learn from poets.

Make every word count.

Poets truly know how to craft the most expressive words into economical form, whittling and pruning until the minimum remains. Remove filler words (e.g., adjectives, adverbs), simplify sentences, and don’t over-explain. In research-led writing, this is extremely useful when writing to strict word counts – whether short-form blogs, journal articles, or a book chapter. I’ve shown my own process with this in the next section.

Listen to the paralanguage of your piece.

Poems are as much about form as they are about words. Rhythm and cadence are essential to the generate meaning and beauty in a poem, and they emerge primarily from sentence length and line breaks. To work with hear the ‘music’ of your writing, start by tuning first tune into your sentences. Read them aloud. Are they all the same length? Do you seem to have a preference for long ones? Short Snappy statements? Split clauses? Try varying them. Long sentences create movement because their clauses run on, helping readers feel they’re hurrying - maybe even running - alongside you as you head on your journey. Long sentences can also lingerin the slowness of with languid language, as you patiently explain a concept that’s important and worth your reader’s time. But then stop. Dead. See? Think Shorter sentences are great for mic drop moments and instructions.

Play with ‘white space’

Poets leave gaps on the page so ideas can breathe, hanging in the reader’s mind for emphasis. Short lines, large spaces between them, columns, right justification or typeset patterns are all spatial devices to play with words on a page. If you are writing creative nonfiction or for a non-traditional academic journal, have fun with form and see how it shifts the meaning of the text. One of my clients used two columns for the findings chapters of her thesis, for example, to write from two identity positions at the same time.

Value repetition

Alliteration - the repeated sound of the same initial letter of a string of words - can help build a mood. And yes that’s important in research-led writing too, especially where qualitative data is being presented. Why? Because you want your reader to feel your data and inhabit the story you are telling. Assonance – the repetition of similar sounds - helps vary rhythm: from pace, to race, with grace. And when repeating metaphor, don’t mix them up: for example you can view through the lens of a theory, but you can’t discuss through one.

Poets are maestros of pace, energy and emotion and they work with quite astonishing linguistic economy. The worlds they conjure from only a few choice words meticulously arranged, are testament to how poems bloom reader’s imaginations from nothing but a few impressions. Since hooking your reader quickly is imperative in these days of lightning-fast attention-loss, it stands to reason that all writers can borrow from the poet’s toolbox to engineer sentences that keep our readers on the page. Whether you have 800 words or 8000 to craft, for a blog, a book, an article or a thesis, who better to turn to for inspiration than poets?